Nanni Balestrini's book Vogliamo Tutto (and recently translated by Matt Holden for Telephone Publishing - later my review of the translation will appear elsewhere) was the ultimate literary work associated with this book. Yet what about popular song? How did the Hot Autumn find its way there?

|

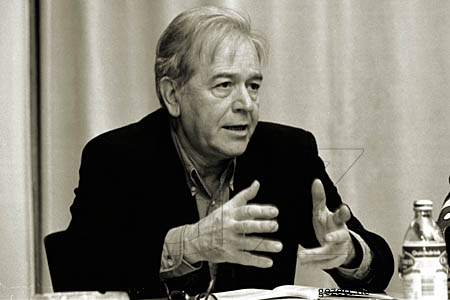

| Nanni Balestrini, the author of Vogliamo Tutto, the literary work which symbolised Italy's Hot Autumn of 1969 and the revolt of the 'mass worker' |

Gaetano also sung another song related more obliquely to the emigration of southern workers north and a sense of anarchic revolt in his Agapito Malteni, il ferroviere about an engine driver who started off as an obedient Catholic but then became tempted by emigration north and revolt against his lot in the South:

Gaetano was not the only one to talk about emigration from the south to the north and the destiny of the internal immigrant to become the 'mass worker' radicalising the revolt at FIAT.

Lucio Dalla in his 1973 album Il Giorno aveva cinque teste (The Day Had Five Heads) also sang of the fate of a family of southern immigrants travelling to Turin in desperate circumstances in his song Un'auto targata TO (A car with a Turin numberplate).

Dalla's song rather than a song of revolt is a description of the conditions that led to revolt. Lucio Dalla is not thought as a committed singer but here in this album (where he began his collaboration with Bolognese poet Roberto Roversi) the social theme comes to the forefront. Dalla also sings about work-related accidents and emigration in his song L'operaio Gerolamo (The worker Gerolamo):

A few songs are included in this documentary on the Hot Autumn which gives a good overall indication of the atmosphere of the period and some of the more directly political songs of the time. In many ways the ultimate song of workers autonomy and unrestrained revolt could be seen in a famous song by Francesco Guccini La Locomotiva (The Locomotive) which recounts the story of an anarchist engine driver who commandeered an engine at the end of the 19th century and deliberately intended to crash his engine as a symbol of protest against injustice. Not influenced by the Hot Autumn the song was a symbol of its period in which

La bomba proletaria illuminava l'aria

e la fiaccola dell'anarchia

(The proletarian bomb illuminates the air

and the flame of anarchy

Gaetano was not the only one to talk about emigration from the south to the north and the destiny of the internal immigrant to become the 'mass worker' radicalising the revolt at FIAT.

Lucio Dalla in his 1973 album Il Giorno aveva cinque teste (The Day Had Five Heads) also sang of the fate of a family of southern immigrants travelling to Turin in desperate circumstances in his song Un'auto targata TO (A car with a Turin numberplate).

A few songs are included in this documentary on the Hot Autumn which gives a good overall indication of the atmosphere of the period and some of the more directly political songs of the time. In many ways the ultimate song of workers autonomy and unrestrained revolt could be seen in a famous song by Francesco Guccini La Locomotiva (The Locomotive) which recounts the story of an anarchist engine driver who commandeered an engine at the end of the 19th century and deliberately intended to crash his engine as a symbol of protest against injustice. Not influenced by the Hot Autumn the song was a symbol of its period in which

La bomba proletaria illuminava l'aria

e la fiaccola dell'anarchia

(The proletarian bomb illuminates the air

and the flame of anarchy

|

| Francesco Guccini was to write and perform the song which illuminated the revolt set off by the Hot Autumn- La Locomotiva |

Of course, the political group most associated with the mass workers revolt at FIAT Potere Operaio used as their song an old Polish and then Russian revolutionary song the Varshavianka which was then transformed into Stato e Padroni as their hymn: